CAST’s co-founder Matt Hutchins, AIA, CPHD, and Seattle Planning Commissioner talks about the major update to the Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan.

one seattle for all - 2025/02/08 10:37 PST – Recording

Seattle is growing (and that’s good)!

How do we make room for new housing and be the kind of city we want to live in?

Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan major update – a 20-year growth strategy.

- Must include affordable housing and middle housing

- Housing planning aligns with planning for transportation, utilities, climate and the environment, capital

facilities and parks/open space

Two kinds of affordable housing:

1. Subsidized and deeply affordable

2. Less expensive housing by size, type, and age (ie. ADUs, small apartments

- Neighborhood centers can hold both types of affordable housing

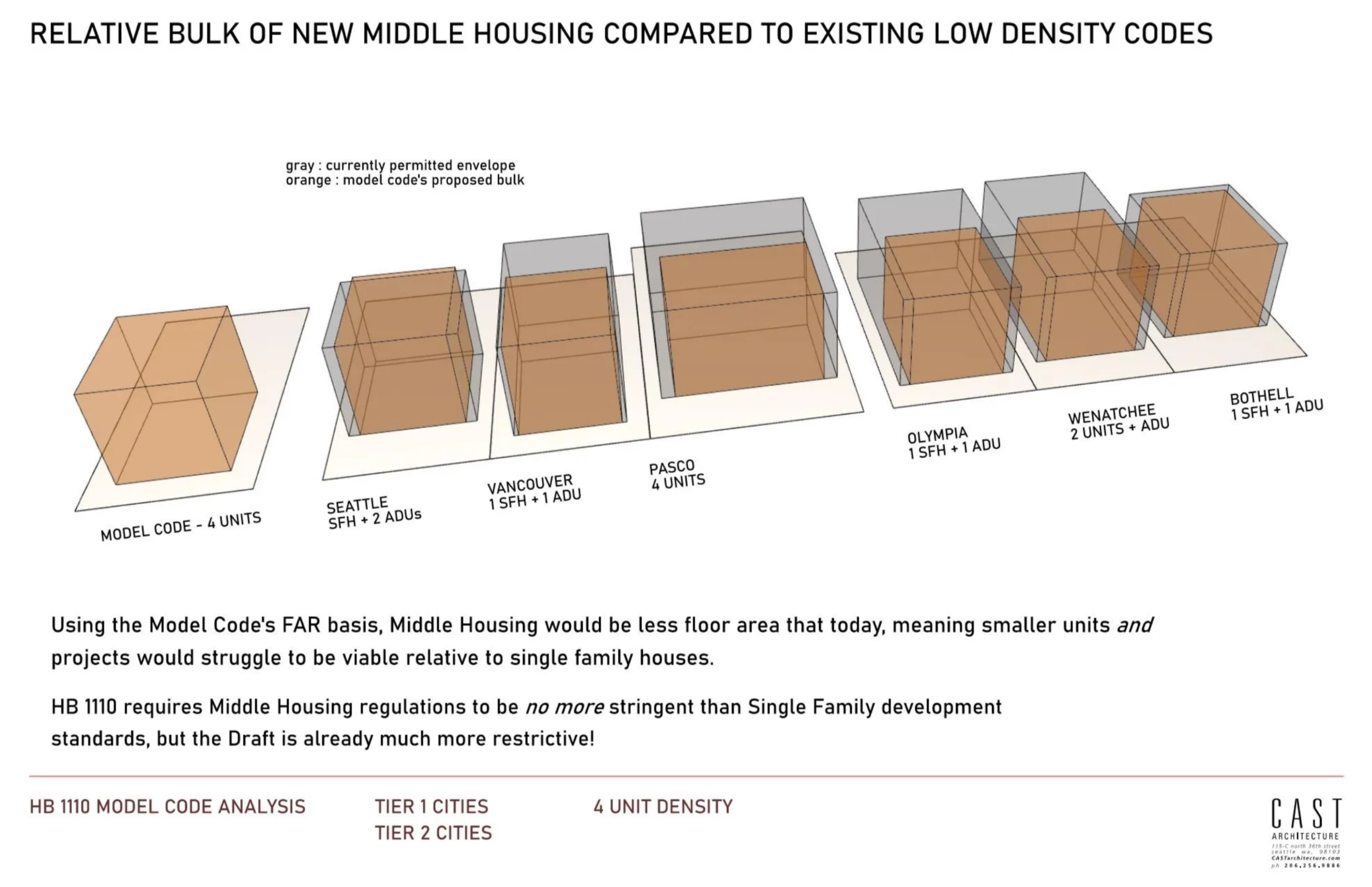

- Middle housing is less expensive and a great option

- Urban Neighborhood housing types: single-family housing with ADU, duplexes, townhomes, stackedflats

We need more affordable housing – where does it go?

- Neighborhood centers can support both types of affordable housing

Let your city council member know you support affordable housing, and you also support neighborhood centers and middle housing.

oneseattleforall.org